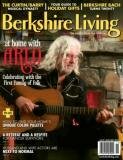

Plain Folk

All is quiet in the church. Incense smoke ribbons through the air amid rays of sunlight that stream through a beautifully ornate window, in front of which there is a shrine: a Buddha sits shoulder to shoulder with a Christian pietà, which sits next to a Jewish hannukiah, all surrounded by candles and religious and spiritual symbols of many other denominations.

It is the calm before the storm of a concert. Arlo Guthrie’s four adult children are expected to arrive at any second. But until they do, the atmosphere inside the church is, well, churchlike. Then, suddenly, the doors to the former Trinity Church in the Van Deusenville section of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, open, and children run in, giggling, followed by Abe and his wife, Lisa; Cathyaliza (known to all as Cathy); Annie; and Sarah Lee Guthrie and her husband, Johnny Irion, with more kids in arms. They are smiling and hugging and nurturing, siblings offering to fetch food for each other’s kids. Shoulders are patted and toddlers are passed from arms to arms to arms as they all settle into sofas and cozy chairs. As the musicians prepare for the concert, their eyes are wide, their gazes invested and present, smiles bright. Their eyes all say Arlo, and their huge smiles bear the imprint of their mother, Jackie. Their realness as human beings, as down-to-earth folkies, born to the manner, is written across their faces.

The Guthries are known as the “First Family of Folk.” I’ve heard this title thrown around for a long  time, and to me it has always meant that they carry the honor, mystique, “nobility” as it were, that comes from being descendants of Woody Guthrie, the most influential folksinger of the twentieth century, and in turn, of his son, their father, Arlo Guthrie. The “First Family” moniker is a badge of honor that separates them, places them higher than others, suggestive more of the children of presidents than folksingers, a silly title perhaps for anything associated with folk music, which in many ways stands for a rejection of the culture of titled nobility and aristocracy.

time, and to me it has always meant that they carry the honor, mystique, “nobility” as it were, that comes from being descendants of Woody Guthrie, the most influential folksinger of the twentieth century, and in turn, of his son, their father, Arlo Guthrie. The “First Family” moniker is a badge of honor that separates them, places them higher than others, suggestive more of the children of presidents than folksingers, a silly title perhaps for anything associated with folk music, which in many ways stands for a rejection of the culture of titled nobility and aristocracy.

Rather, if the three generations gathered this day at the Guthrie Center are the First Family of Folk, it’s as much because fame and commercial success are not high on their list of priorities. For the Guthries are all about home, land, music, nature, truth, and community on the most basic levels—the very stuff of Woody Guthrie songs like “Pastures of Plenty” and “This Land Is Your Land.” Their music, like his, is completely honest and organic. They use it to challenge, to provoke, to connect people, and to connect themselves to the world. What makes them the First Family of Folk is even reflected in the place they call home—not some White House or grand palatial estate or former industrialist’s summer cottage, but a regular old farmhouse at the end of a dirt road in the quiet hilltown of Washington, Massachusetts.

In the summer of 1969—the summer of the Woodstock Music and Arts Festival, where Arlo Guthrie was a headliner—Arlo decided that his apartment in the very happening Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan was not going to be the place he and his wife, Jackie, then pregnant with their first child, Abe, were going to sow seeds and grow a place to call home. That decision has everything to do with why the Guthrie children, and now grandchildren, look you in the eye and speak  with their hearts and minds alert and open. You can even hear it in their voices, which are imprinted with the unique cadences of the eastern hilltowns of the region: they’re rural, small-town Berkshire folk, right to the core.

with their hearts and minds alert and open. You can even hear it in their voices, which are imprinted with the unique cadences of the eastern hilltowns of the region: they’re rural, small-town Berkshire folk, right to the core.

“Jackie and I still look at each other, even now, and say it’s the smartest thing we ever did,” Arlo says of their move from New York City to the woods of the Berkshires. “When you’re working in music, you’re working with a lot of people. And it’s really the contrast that I love. It’s good to get away from all of that…. When you go home, you go home. [Living here in the Berkshires] is a kind of old-style America that really doesn’t exist very many other places anymore. We’ve got great neighbors here. People take care of you here. They’re neighbors in the old sense of the word. There’s no better place to be, as far as I’m concerned.”

Born in 1947, Arlo started visiting the Berkshires from his hometown in the Coney Island section of Brooklyn as a child of ten or eleven when his mother, Marjorie Mazia Guthrie, who was a Martha Graham dancer, would teach dance at Indian Hill, a summer arts workshop in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Woody Guthrie would also come to the Berkshires, where he performed at the burgeoning Berkshire Music Barn, later to become the Music Inn. When it came time to attend high school, Arlo chose the Stockbridge School, an alternative, educationally progressive, integrated boarding school, the campus of which later became the now-defunct DeSisto School. So the Brooklyn-raised Arlo Guthrie actually spent a good portion of his developmental years in these  environs, not far from where he would eventually settle down to raise a family and preside over a folk music dynasty.

environs, not far from where he would eventually settle down to raise a family and preside over a folk music dynasty.

In 1969, at the same time the Arthur Penn-directed film, Alice’s Restaurant—based on the Guthrie song recounting a fateful Thanksgiving Day meal at the church and its aftermath—was being released, Arlo and Jackie found their property in Washington. They got married there and have lived there ever since. It was originally a farm consisting of a traditional farmhouse, more than two hundred years old, and a hunting cabin. “These days,” Arlo says, “Jackie and I live in the hunting cabin, and Abe and his family live in the house.”

The Guthries couldn’t have chosen a better spot for the small-town life that Arlo sought out as a refuge from the madness of the music business. Washington is such a small town that it actually shares a school, a post office, a library, and other amenities with a bordering town, Becket. Those who grew up in Becket when the Guthrie children were small (as did this writer) are familiar with that certain hilltown something that Arlo calls “old-style America.”

Back then, it looked something like this. Daybreak: a mist rises in the parking lot between the Becket Arts Center and the white clapboard Athenaeum. Across the street at the Becket General Store, Bob Gerner has just returned with the morning doughnuts and crullers from the Morningside Bakery in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Macrobiotics pioneer Michio Kushi wanders down the road from the Kushi Institute for some coffee. The young Bobby Sweet, who lives in a house behind the general store and who will grow up to be one of the region’s best-known musicians, comes in to keep warm while he waits for the school bus. Arlo Guthrie pulls up in his boat of an old car, sweeps the long hair under his hat, and fills up at the gas pump. The town police chief is in for coffee and conversation at the counter, after having milked his cows hours earlier. A local farmer delivers eggs, says hello to everybody by name, pays a phone bill at the counter, slaps up a sign that he’s got firewood for sale, nabs six customers within twenty seconds, and returns a couple of videos to the town librarian, who also happens to be sitting at the counter eating a cruller and sipping coffee.

Arts Center and the white clapboard Athenaeum. Across the street at the Becket General Store, Bob Gerner has just returned with the morning doughnuts and crullers from the Morningside Bakery in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Macrobiotics pioneer Michio Kushi wanders down the road from the Kushi Institute for some coffee. The young Bobby Sweet, who lives in a house behind the general store and who will grow up to be one of the region’s best-known musicians, comes in to keep warm while he waits for the school bus. Arlo Guthrie pulls up in his boat of an old car, sweeps the long hair under his hat, and fills up at the gas pump. The town police chief is in for coffee and conversation at the counter, after having milked his cows hours earlier. A local farmer delivers eggs, says hello to everybody by name, pays a phone bill at the counter, slaps up a sign that he’s got firewood for sale, nabs six customers within twenty seconds, and returns a couple of videos to the town librarian, who also happens to be sitting at the counter eating a cruller and sipping coffee.

The same atmosphere prevails today. It’s a low-key, kicked-back way of life into which the Guthries fit perfectly. Intense isolation is mixed in with intense friendships. Generally, people in the hilltowns spend more time alone, but they also depend upon and appreciate one another more than people in  an urban area. It’s a haven for artists, loners, natives whose families have been there for five generations, and city transplants who need room to think. It makes for a perfect bohemian blend, resulting in “the Topanga Canyon of the East Coast,” as Sarah Lee Guthrie describes it. “Lots of freaks, and we consider that to be a good thing.”

an urban area. It’s a haven for artists, loners, natives whose families have been there for five generations, and city transplants who need room to think. It makes for a perfect bohemian blend, resulting in “the Topanga Canyon of the East Coast,” as Sarah Lee Guthrie describes it. “Lots of freaks, and we consider that to be a good thing.”

Milton, a New York musician and a friend of the Guthries who has spent time in Becket since he was a kid and who frequently performs at that other rural oasis, the Dream Away Lodge, describes Becket as a “holy ground” for musicians and artists. “It’s rare that artists can find a place to do their thing freely and be free to breathe the air and dig the country at the same time.”

“We would go on tour with dad,” says Annie Guthrie, “but this was always home, and we were always free. I would go out in the woods in the morning and be gone all day and come home dirty and filthy. I love the community here; I think it’s really romantic and has a lot of charm. It’s one of the few places that is really untouched.”

It was also a place where Arlo and Jackie could instill their strongly held values in their children relatively free of the noise of the prevailing culture. Annie recalls an emphasis on making the world a better place by serving others. “We were not raised in any one religion,” she says. “It was what my parents called an ‘interfaith experience.’ Dad had done a lot of soul-searching on his own. He has walked a lot of different paths to find what was right for him. And my grandfather had started that search.” Annie recalls a story about the time Woody entered a hospital and had to fill out a form identifying his religion; he wrote, “All and none.”

Arlo was raised Jewish by his mother and, more so, by his grandmother, the famous Yiddish poet and lyricist, Aliza Greenblatt, affectionately known as “Bubbe” to all, who lived across the street from Marjorie and Woody, enabling her to watch after Arlo and his younger sister, Nora, while Marjorie was dancing and while Woody, who spent several years in California in the early 1950s, was on the road. (By the time Arlo turned nine-years-old, Woody was hospitalized for the Huntington’s disease that would eventually take his life in 1967; thus Bubbe was, in large part, Arlo and Nora’s primary caretaker.) Rabbi Meir Kahane, who later founded the Jewish Defense League, was the local rabbi who presided over Arlo’s bar mitzvah service.

“Woody,” Annie says, “well, he was a variety of things. My own mother was Mormon, but she’s now interfaith also.” Sarah Lee and Annie spent time at an interfaith ashram in Florida during high school. “Our parents didn’t push religion on us. They would answer questions with their hearts. Our parents’ religion is kindness.”

Their “religion” seems to permeate all aspects of their family dynamic. Annie describes a commitment to each other and each other’s kids. When one or another sibling has to go to a gig, the children sometimes spend weekends with cousins at each other’s homes. The young cousins are Annie’s children, a son, Shiva Das (they call him Mo), and daughter, Jacklyn; Abe’s son, Krishna, and daughter, Serena; Cathy’s daughter, Marjorie; and Sarah Lee’s daughters, Olivia and Sophia. Most of them attend the local public schools of the Becket/Washington district.

Nathan Hanford, an artist now living in London who grew up in Becket with the Guthries, says: “In the early seventies, the Guthrie family was an example of living close to nature, holding family close, cherishing friendships ... and beyond that, having a greater respect for it all. The family had a strong identity; even the car they drove stood out from the rest. It was this awesome old vintage thing, I think a Ford or Chevrolet. In a time when my folks let go of farming and slipped a little towards the whole ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ culture, the Guthries still held strong to their identity as creators,  a family, and as people.”

a family, and as people.”

Kate Barber, whose parents are both artists and who comes from something of a legendary Berkshire family herself (her grandmother was Stephanie Barber of Music Inn fame, and her uncle is Benjamin Barber, the renowned political theorist), remembers the Guthries as “modest, down-to-earth, and delighted in the Berkshire mountains. They were absolutely as average-Joe, albeit with famous lineage, as the rest of us. It was a refreshing slice of childhood innocence that our classmates never cared who they were. I don’t remember when I realized that Annie and Sarah’s dad was famous. I don’t remember it occurring to me that my friends’ grandfather was the legend my own dad listened to and spoke of endlessly.”

It’s precisely this anti-celebrity culture that keeps the Guthries rooted here. “The hilltowns keep me  grounded and down to earth,” Sarah Lee says. “I was just in Denver, for example, last Friday, and we were getting ready for the show, when I got a call from the Becket General Store letting me know that my Berkshire Mountain Bread was in. That’s one of the reasons we actually moved back here after living in Columbia, South Carolina, for seven years. We do so much traveling and meet so many people and are so drenched in popular culture that it is really nice to come home and get down to the basics, the things that really matter: good food from the garden, good milk and meat from the farm, and good friends at the Dream Away. Oh yes, and, of course, the family. It’s really important for us to have that balance; it reminds us of what we are here for, of what’s important.”

grounded and down to earth,” Sarah Lee says. “I was just in Denver, for example, last Friday, and we were getting ready for the show, when I got a call from the Becket General Store letting me know that my Berkshire Mountain Bread was in. That’s one of the reasons we actually moved back here after living in Columbia, South Carolina, for seven years. We do so much traveling and meet so many people and are so drenched in popular culture that it is really nice to come home and get down to the basics, the things that really matter: good food from the garden, good milk and meat from the farm, and good friends at the Dream Away. Oh yes, and, of course, the family. It’s really important for us to have that balance; it reminds us of what we are here for, of what’s important.”

The only Guthrie child not currently living within a shout or a short drive from her childhood home is Cathy, whom the other siblings are trying to woo back from Austin, Texas. “I bug her almost every day. I know she’d like to be here; it’s only a matter of when,” Sarah Lee attests. “Cathy’s had her eye on a certain place here for a while,” Arlo reiterates.

Raising a family in this rural oasis also made it easier for Arlo to instill his forebears’ musical traditions in his children. Annie chuckles at the memory. “We had music here every single day, but our parents never told us what we kids were going to be. Music would be a part of our lives regardless of who we would become.” Annie originally wanted to be a dancer. Cathy, the self-described black sheep of the family, went to college and studied business management. Abe was a musician from the start, but as Annie tells the story, Arlo never wanted to push music on any of them as a career, to the point that he would only teach them the hardest songs, “the ones that hurt your fingers the most and were the most difficult,” to test how badly they really wanted to learn.

One by one, each child came to music on his or her own. All four have full-fledged music careers of their own now in addition to playing together. Sarah Lee often plays as a duo with her husband, Johnny Irion, and Cathy plays with Amy Nelson, daughter of Willie Nelson, in the duo Folk Uke.

Their children, Arlo’s grandchildren, however, have had a different experience. Says Sarah Lee, “My kids have both grown up on the road with us and are very involved in our music career. Olivia has actually helped us write and record our most recent album, Go Waggaloo.”

Annie took her children out of school for a year so that they all could tour together with the Guthrie Family Rides Again Tour. “The kids are really happy that they got to go out and sing every night and be a part of the tour and spend time with each other,” Annie says. “Playing music together is completely different than playing by the pool.” This, she says, was Woody’s ultimate dream, that he would create a huge family that would play music together. “We’ve done it,” Annie says. “And we actually like each other. Even after spending a year, seventeen of us, on a forty-five-foot bus together.”

And that, as much as anything, accounts for why the Guthries are America’s First Family of Folk. [NOV/DEC 2010]

Juliane Hiam is a freelance writer in Pittsfield, Mass. This is her first story for Berkshire Living.

THE GOODS

The Guthrie Center

.

Great Barrington, Mass.

Arlo Guthrie in Concert

Nov 20 at 8

Colonial Theatre

/

Pittsfield, Mass.

Cathy Guthrie (and Amy Nelson)

Sarah Lee Guthrie and Johnny Irion

THE REST OF THE STORY

A CONVERSATION WITH ARLO GUTHRIE

Join us on Sunday, December 5, at 11 a.m., at the Triplex Cinema in Great Barrington, Mass., for a conversation with folksinger Arlo Guthrie, as part of the award-winning Rest of the Story series of free public forums moderated by Berkshire Living editor-in-chief Seth Rogovoy.

Due to limited seating and the special nature of this event, advance reservations are required. Send your reservation requests to .

For more information call .

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati