THE BEAT GOES ON: The Boss's Lost Promise

How do you follow up the greatest album in rock ’n’ roll history? This was the problem Bruce Springsteen faced after the late-summer 1975 release of Born to Run, the record that put him on the cover of Time and Newsweek in the same week in October, instantly pegging him as the savior of rock ’n’ roll.

How do you follow up the greatest album in rock ’n’ roll history? This was the problem Bruce Springsteen faced after the late-summer 1975 release of Born to Run, the record that put him on the cover of Time and Newsweek in the same week in October, instantly pegging him as the savior of rock ’n’ roll.

Conventional wisdom at the time would have had Springsteen follow up the huge critical success of Born to Run with an album rushed to market in early 1976, something perhaps in the same vein as its predecessor but slightly more commercial (oddly enough, Born to Run produced no hit singles). In a curious twist, Springsteen was saved from that fate due to a legal tangle with his manager that effectively kept him out of the recording studio for two years. While his career may have lost momentum as a result (although he continued touring, enhancing his reputation along the way as a phenomenal live performer), the forced time off saved him from recording and releasing a half-baked effort and colored the work that finally stood as the official sequel to Born to Run, 1978’s Darkness on the Edge of Town.

When it first came out, Darkness was shocking in its lack of resemblance to Born to Run and the albums that preceded it. Gone were the dramatic, romantic epics, the operettas of teen lust and love like “Rosalita” and “Jungleland” that owed as much to William Shakespeare and Leonard Bernstein as they did to James Dean and Roy Orbison. In their place were stark portraits of being stuck in dead-end jobs in nowhere towns and shattered romantic dreams. If Born to Run was about cutting loose and getting free (“Tramps like us/ Baby we were born to run”), Darkness was about stasis, dismay, and loss of idealism (“You’re born with nothing, and better off that way/ Soon as you’ve got something they send someone to try and take it away”).

The mood of the music on Darkness matched its lyrical content. Where Born to Run was revved up R&B, full of swinging horns, swooping strings, keyboard glissandos, and Clarence Clemons’s jazzy saxophone riffs, Darkness was mostly a stripped-down affair—mournful ballads and grim rockers, the horns replaced with Springsteen’s own sharp, stinging guitar licks and vocal howls and moans. Even the album art reflected the change—the Boss shared top billing with Clemons on the cover photo of Born to Run, the two of them, instruments in hands, “all duded up for Saturday night,” whereas Springsteen appeared alone on the cover of Darkness, posed in front of closed venetian blinds and looking like he just got home from working an eight-hour shift on the assembly line.

Late last year, Columbia Records repackaged Darkness on the Edge of Town in a massive box set called The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story, which, in addition to a much-needed digitally remastered version of Darkness, includes two CDs comprising The Promise (also available separately as a two-CD set) and three DVDs—two featuring vintage 1970s concert footage and a third containing a documentary film about the making of Darkness on the Edge of Town. (No major artist has suffered as much as Springsteen in the transition from analog to digital; his albums have never sounded as warm on CD or in digital files as they originally did on LP; the remastered version, like 2005’s thirtieth-anniversary edition of Born to Run, goes a long way toward improving that technical problem.) The box set also includes an eighty-page notebook containing facsimiles from Springsteen’s original notebooks from the recording sessions, which include alternate lyrics, song ideas, recording details, and personal notes, plus a new essay by Springsteen and tons of archival photos.

Late last year, Columbia Records repackaged Darkness on the Edge of Town in a massive box set called The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story, which, in addition to a much-needed digitally remastered version of Darkness, includes two CDs comprising The Promise (also available separately as a two-CD set) and three DVDs—two featuring vintage 1970s concert footage and a third containing a documentary film about the making of Darkness on the Edge of Town. (No major artist has suffered as much as Springsteen in the transition from analog to digital; his albums have never sounded as warm on CD or in digital files as they originally did on LP; the remastered version, like 2005’s thirtieth-anniversary edition of Born to Run, goes a long way toward improving that technical problem.) The box set also includes an eighty-page notebook containing facsimiles from Springsteen’s original notebooks from the recording sessions, which include alternate lyrics, song ideas, recording details, and personal notes, plus a new essay by Springsteen and tons of archival photos.

Taken as a whole, it is a massive, pricey package, but it succeeds in its aim at opening a window on Springsteen’s creative process at this turning point in his career. The documentary film in particular exposes Springsteen for the master control freak that he was and always has been—and I mean this in the best possible way. He knew what he was after, and he wouldn’t let the influence or opposition of anyone stop him from getting it, even to the point of driving his fellow musicians, producers, and engineers bonkers.

The two dozen songs from the Darkness sessions that constitute The Promise also demonstrate Springsteen’s wisdom in releasing the album the way he did. The songs on The Promise bear more in common with his subsequent album, 1980’s The River. They could have been released as Another Side of Bruce Springsteen, so different are they really from anything else that he recorded up until then. They hark back to the early New York rock ’n’ roll of Dion and the Belmonts, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, and other Italian rockers who so strongly influenced Springsteen, as well as Buddy Holly, the Byrds, and Phil Spector. At times the songs as performed by the Boss and the E Street Band sound more like Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes—indeed, the latter recorded some of these tunes, and some of the horn players from Southside’s band lend a hand here. There are a few clunkers—did we really need to hear earlier, crappier versions of the songs that would become “Racing in the Street” and “Factory”? (No)—but for the most part, The Promise is one of Springsteen’s most infectious albums, one that could have undoubtedly produced a string of pop hits (and one that did, for other artists, such as the Pointer Sisters’ version of “Fire” and Patti Smith’s improved rendition of “Because the Night”) had it been released in 1978—or 1988 or 1998, for that matter.

We come to understand, however, that this is precisely why Springsteen withheld these songs in favor of Darkness on the Edge of Town, the album that introduced a new Bruce Springsteen—a more somber, terse chronicler of America’s lost promise. After only a brief left turn for The River (really two albums in one, an attempt to have it both ways with Darkness-like ballads and Promise-like party tunes), this is the Springsteen who would adopt a middle-American twang for Nebraska on his way toward the global superstardom that followed Born in the U.S.A.

We come to understand, however, that this is precisely why Springsteen withheld these songs in favor of Darkness on the Edge of Town, the album that introduced a new Bruce Springsteen—a more somber, terse chronicler of America’s lost promise. After only a brief left turn for The River (really two albums in one, an attempt to have it both ways with Darkness-like ballads and Promise-like party tunes), this is the Springsteen who would adopt a middle-American twang for Nebraska on his way toward the global superstardom that followed Born in the U.S.A.

The Springsteen who made those albums and all his subsequent ones was not the Boss of Born to Run. For better or worse, Springsteen left him behind. For my money, it was for worse—the hokey, affected twang and the Steinbeckian social portraiture has always rung a little false; Springsteen seems at his most effortlessly creative and honest as the R&B-inflected street poet of his earlier albums.

Nevertheless, and now seen and heard in context, in retrospect, and with its improved sound, Darkness on the Edge of Town certainly stands tall as one of the all-time greatest rock albums, a work of meticulous perfectionism that so perfectly captures a sense and a mood and a time in American history when, indeed, brute reality crushed whatever romanticism or idealism lingered from the 1960s. Springsteen says that he strongly identified with the punk-rock that was contemporaneous with Darkness, and indeed, in message and attitude, they shared a close kinship. If we lost the greatest rock ’n’ roll romantic to the collapse of our industrial might, economic recession, and Ronald Reagan’s false promise of morning in America, we can’t well pin the blame on the romantic himself. Springsteen explains this dilemma best when in “The Promise” he sings, “When the promise is broken you go on living/ But it steals something from down in your soul.” [FEB/MAR 2011]

THE GOODS

The Promise: The Darkness on the Edge of Town Story

Columbia

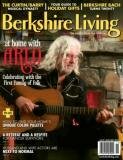

Seth Rogovoy is Berkshire Living’s award-winning editor-in-chief and music critic and the author of Bob Dylan: Prophet Mystic Poet. Read more of his music reviews at www.berkshireliving.com.

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati