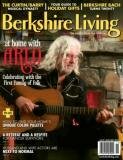

Taylor Made

It’s a gorgeous, early June morning, and James Taylor has just returned from his daily morning row  on a nearby lake. Still wearing his wader boots, an old pair of jeans, a plaid, short-sleeve flannel shirt, a baseball cap, and his wire-rim eyeglasses, the tall, lanky singer-songwriter is deep in conversation with a three-man construction crew that’s transforming a barn-like structure just a few steps from his house into a multi-purpose building that will eventually house a rehearsal space, recording studio, office, storage facility, and chill-out room.

on a nearby lake. Still wearing his wader boots, an old pair of jeans, a plaid, short-sleeve flannel shirt, a baseball cap, and his wire-rim eyeglasses, the tall, lanky singer-songwriter is deep in conversation with a three-man construction crew that’s transforming a barn-like structure just a few steps from his house into a multi-purpose building that will eventually house a rehearsal space, recording studio, office, storage facility, and chill-out room.

Taylor, 59, breaks off from the progress report on the construction site and leads a visitor downstairs to his garage workshop, where he likes to lose himself in projects ranging from fixing kids’ toys to building rough furniture. “I’m not a great carpenter, but I’m not bad, either,” he says in his typically understated style.

He points to an air compressor. “[My bassist] Jimmy Johnson sent it to me,” he says. “I have no idea why. Jimmy sends me lots of tools—he sent me that vice grip and a soldering iron. But this one really has me stumped.”

Toward the rear of the workshop through a door, Taylor shows off his storage room, filled with trunks of all sizes, enough almost to fill a semitrailer. Inside are instruments and sound equipment, the tools of the trade when Taylor is on tour. He opens one to reveal a portable wardrobe, replete with shirts on hangers and drawers full of anything he might possibly need while on the road, including throat spray, lozenges, guitar picks, capos, tape, and even some stuff he doesn’t need, like a souvenir he was given on a recent trip to Scotland: a skirted flask. “Great,” he jokes. “Just what I need. Over twenty years of sobriety all down the drain because of this.”

Still deeper into the room, there’s another, unfinished space: a cool, dry area where one might expect to find a wine cellar if its owner hadn’t quit drinking decades ago. Instead, Taylor shows off what’s going to be a guitar cellar: a climate-controlled room dedicated to housing his eighteen axes and other instruments.

Those guitars have graced the nearly two-dozen albums (including various collections and best-of packages) that Taylor has recorded over the course of the last four decades, along the way helping to garner the Boston native by way of North Carolina over forty gold, platinum, and multi-platinum awards for albums running from 1970’s Sweet Baby James to 2002’s October Road, as well as the 1998 Century Award, Billboard magazine’s highest accolade, bestowed for distinguished creative achievement, and places in both the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the prestigious Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. Those guitars have fueled hit singles including “Your Smiling Face,” “How Sweet It Is  (To Be Loved By You),” and “Fire and Rain,” and fan favorites such as “Carolina In My Mind,” “Steamroller Blues,” and “Something in the Way She Moves.” They’ve traveled the world with Taylor, who, unlike many of his peers, has never retired from the road and continues to perform relentlessly.

(To Be Loved By You),” and “Fire and Rain,” and fan favorites such as “Carolina In My Mind,” “Steamroller Blues,” and “Something in the Way She Moves.” They’ve traveled the world with Taylor, who, unlike many of his peers, has never retired from the road and continues to perform relentlessly.

But it’s only fitting that his guitars will be given a proper home, as Taylor himself finally seems to have settled comfortably into his house at the edge of a state forest down a long, country road in the town of Washington, Massachusetts. Not that he’s about to sit around and do nothing but chill out here: he’s planning future tours, DVDs, and recordings, and has a list of projects to take him through at least the next ten years.

But as he takes a visitor on a guided tour of the rooms in the barn—all within shouting distance of his bedroom—it’s clear that Taylor has finally found a place to call home: a base from which to conduct his life’s work, as well as where he and his wife, Caroline—best known as Kim—have decided to raise their twin six-year-old boys, Rufus and Henry.

Taylor is, of course, no stranger to these parts. He first came to the Berkshires in 1968 as a twenty- year-old seeking help at Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. It was a troubled time in his life, when he was battling depression and drug addiction, and he’s spoken candidly about it over the years, including a now obligatory shout-out to the place every time he performs at Tanglewood just up the road in Lenox.

year-old seeking help at Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. It was a troubled time in his life, when he was battling depression and drug addiction, and he’s spoken candidly about it over the years, including a now obligatory shout-out to the place every time he performs at Tanglewood just up the road in Lenox.

He returned a few years later to hang out with his best friend, Zach Weisner, and his fellow musician pal Arlo Guthrie, and then again periodically to perform at Tanglewood in the 1970s—when the venue regularly featured folk, pop, and rock artists. That is, until Taylor suspects he was informally banned from the place after a show during which one of his road crew members drove on the lawn and left some deep ruts. “The groundskeepers were very upset,” says Taylor wryly.

Of course the ban didn’t last long, and now Taylor’s annual appearances at Tanglewood are practically as traditional as Tanglewood on Parade, the fireworks at the Independence Day festivities, and the season-concluding Beethoven’s Ninth. (In fact, a few summers ago, when Taylor failed to appear as a headliner, local hoteliers raised a stink, protesting that the Boston Symphony Orchestra was costing them huge amounts of revenue by not scheduling a Taylor show—a dubious proposition, but one that seems to have gotten the attention of the BSO.)

This month, Taylor returns once again in a headlining gig (the show, on August 24 [2007], has long been sold out). But things will be different this time around. Rather than performing with his eleven-piece ensemble, including a horn section, backup vocalists, and a percussionist in addition to a drummer, Taylor will present his “One Man Band” show at Tanglewood.

Despite the title, the concert actually includes keyboardist Larry Goldings, but it has the look and feel of a solo show, albeit one tailored for the digital age and to people’s shrinking attention spans. Taylor will occasionally trot out his self-constructed “time machine,” a homemade drum kit he can operate with foot pedals. He’ll also be backed up on a few numbers by singers from the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, who prerecorded their parts a few years back in Taylor’s barn and will accompany Taylor on video screens strategically placed inside and outside the Shed.

Despite the title, the concert actually includes keyboardist Larry Goldings, but it has the look and feel of a solo show, albeit one tailored for the digital age and to people’s shrinking attention spans. Taylor will occasionally trot out his self-constructed “time machine,” a homemade drum kit he can operate with foot pedals. He’ll also be backed up on a few numbers by singers from the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, who prerecorded their parts a few years back in Taylor’s barn and will accompany Taylor on video screens strategically placed inside and outside the Shed.

Taylor spoke of a few other surprises he has in store for the Tanglewood show that will make the “One Man Band” claim a little hard to defend. But essentially what he’s attempting to recapture in these performances, which he has been developing over the course of the last two years, is the sense of an intimate coffeehouse gig. Along the way, Taylor reveals a lot about the origins of his  songs in his life. After hearing stories that introduce most of them, many of which are also accompanied by old photographs and other visual aids, even those who swear they pick up lots of autobiographical references in his work will undoubtedly come away with newfound appreciation for the way Taylor subtly incorporates or weaves these bits and pieces into his songs. “Sweet Baby James,” for example, was not written about Taylor himself, but inspired by his nephew James, the first child born to his generation of siblings. And “Carolina in My Mind” was prompted by a Greek sunrise that imbued Taylor with nostalgia for his home state.

songs in his life. After hearing stories that introduce most of them, many of which are also accompanied by old photographs and other visual aids, even those who swear they pick up lots of autobiographical references in his work will undoubtedly come away with newfound appreciation for the way Taylor subtly incorporates or weaves these bits and pieces into his songs. “Sweet Baby James,” for example, was not written about Taylor himself, but inspired by his nephew James, the first child born to his generation of siblings. And “Carolina in My Mind” was prompted by a Greek sunrise that imbued Taylor with nostalgia for his home state.

But more than just autobiography, a listener comes away with an appreciation for Taylor as an intelligent, funny, well-rounded guy—the same one you meet in person. In conversation, talk veers from the minutiae of forestry management (a subject dear to his heart, living as he does on the edge of state forest land), to the social history of his town, to gaining control of his family’s carbon footprint. Sometimes talking to Taylor can seem like schmoozing with Al Gore, Howard Zinn, and Simon Winchester all wrapped up in one.

A lot of this comes through in the “One Man Band” show, which Taylor first rehearsed in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in February 2005, appropriately enough at Berkshire Community College’s Koussevitzky Arts Center, named after the BSO conductor who founded Tanglewood. Just a few days before heading out on the road for his first shows in the new format, he was still tinkering with song order back then, the timing of songs and intros, guitar changes, visual cues, and which stories and jokes to tell. An incredible wit and mimic, in rehearsal Taylor sang a few lines of “You’ve Got a Friend” in a dead-on imitation of Bob Dylan in his odd Nashville Skyline phase, cracked jokes about himself and his ex-wives—including singer Carly Simon, the mother of his musician-children Ben and Sally, and actress Kathryn Walker—mock snored his way through a verse, and even made fun of the Carole King lyric, singing: “Winter, spring, summer, or fall all over.”

The whole one-man band concept is just one aspect of a near top-to-bottom attempt to gain control of and re-create the way Taylor manages his life and career, and it’s inextricably tied up with his decision to call the Berkshires home. Taylor refers to it as his “self-management” phase. Gone are the big-time Hollywood managers and publicists, gone are the record company executives and glad-handlers, many of whose hands dug deep into Taylor’s pockets over the years.

The whole one-man band concept is just one aspect of a near top-to-bottom attempt to gain control of and re-create the way Taylor manages his life and career, and it’s inextricably tied up with his decision to call the Berkshires home. Taylor refers to it as his “self-management” phase. Gone are the big-time Hollywood managers and publicists, gone are the record company executives and glad-handlers, many of whose hands dug deep into Taylor’s pockets over the years.

Like many others who leave the big city to settle in the Berkshires and downscale their careers by taking control, shedding unnecessary layers of corporate bureaucracy that get in the way of or eat into the actual tasks at hand, Taylor is setting up a cottage industry of sorts right here in his relatively modest (by Hollywood standards for sure, and even by some Berkshire standards) compound in the woods, where no fancy cars are in sight, and where he shares space with owls, bobcats, fisher, moose, deer, foxes, coyotes, snakes, mountain lions, and wild turkeys. (Taylor can also speak at great length about the life cycle of the female mosquito, plaguing everyone in the area at the moment, if you ask him.)

For Taylor, it’s not a case of getting away from it all by any means. “I lived for a while in Litchfield County and New York City,” he says. “In Litchfield, everything really pointed back to New York. And having lived on Martha’s Vineyard for years, I’m used to people who move in and want to be the last person allowed in. The Berkshires is itself, yet it draws on the energies of the city. Creative energy. Everything is available here. It’s really alive. It gets a lot of energy from New York and Boston, even some of the energy that the Catskills used to have.”

Kim, 54, calls Taylor in for lunch, which is served in a roomy, screened-in porch with a spectacular view of a valley and hillside miles away. Over a platter of seared, grilled tuna prepared by local caterer Megan Moore, the couple recounts in call-and-response fashion how they arrived at their  decision to raise their sons here—how they came to call the Berkshires home:

decision to raise their sons here—how they came to call the Berkshires home:

Kim: In 2002 I tried to decide where we should raise our kids. We started out in Paris, where it was drizzling and cold, with traffic and pollution. Then we went to a little town in the French Alps, but I didn’t like the way the kids were taught in the preschool. The teachers were sitting around ignoring the kids and smoking cigarettes.

JT: We spent some time in Sun Valley, Idaho, where our manager had a place.

Kim: It was romantic, a beautiful liberal pocket, but so unreal. There didn’t seem to be a solid community.

JT: It’s a resort ski town.

Kim: Yes, but it seemed like such a utopia. Then we ended up in Beverly Hills, in Jackie Collins’s house: all white, white walls, white furniture, white everything. We were constantly running around after the kids with a bottle of Windex.

JT: [As if to a grocer] Excuse me, do you have any white grape jelly?

Kim: It was fun, but we never thought we’d wind up there.

JT: When we finally got back here, man, that felt good.

Kim: We just knew.

JT: We’ve ended up in a pretty good spot. We thank our lucky stars we’re here in the Berkshires.

The Taylors sing the praises of Berkshire Country Day School in Lenox, where they send their boys. And James notes that Kim is particularly at home here, having grown up near Albany, attended Smith College in nearby Northampton, Massachusetts, and worked for the BSO, for which she now serves as an overseer, since 1978. “She’s a turnpike girl,” he says.

Kim’s time at the BSO also provided the Taylors a built-in social network, especially in summer when the orchestra is in town. It was at a Boston Pops concert in 1993 at Symphony Hall conducted by John Williams where the two first met. At the time Taylor was still married and Kim was otherwise occupied; they began dating two years later and married in 2001. That same concert saw the beginning of a personal and professional friendship between Taylor and Williams, who have become frequent collaborators on a wide range of projects, including Williams accompanying Taylor as a pianist and Taylor playing with Williams with other orchestras. Williams also notes that he’s engaged Taylor’s services as narrator for several twentieth-century pieces, including Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait.

“I’d always admired him as a singer-songwriter,” says Williams, “but our first musical meeting was very simpatico.”

Williams is clearly as much a fan of the man as he is of the musician. “He’s an especially gifted man and lovely person,” says Williams. “Really one of the quality survivors of the generation of musicians he comes from. What strikes me about James Taylor and his character is he’s very much in the middle of his road: he has as much future as he has past. The one-man show, the narrative appearances. . . . I expect to see him write and speak more. He has leadership abilities that could lead to avenues as yet unimagined. He has a rich path ahead and enormous potential.”

If Williams is hinting that he could see Taylor enter the realm of politics or at least public policy, it doesn’t come as any great leap to anyone who spends time with Taylor, who holds impassioned views on the current presidential administration—“inept, corrupt, and opaque”—and who broke ![Pair of Hearts: Kim and James Taylor attended the Academy Awards this past February [2007], where James joined Randy Newman to perform his nominated song, “Our Town,” from the animated feature “Cars.” (Photo by Bob Riha Jr/WireImage.com)](/sites/default/files/u11/54.JT_.CarolineT_BobR_12938043_Max.jpg) longstanding practice of staying out of partisan politics by throwing his public support behind John Kerry in the last presidential election.

longstanding practice of staying out of partisan politics by throwing his public support behind John Kerry in the last presidential election.

It’s an area in which Taylor treads very carefully, especially in concert where he says fans don’t come to hear political rhetoric. “I grew up in the South, moved from Boston in 1951 to Chapel Hill,” he says. “It was a liberal pocket amidst the antebellum South. To be in the South at the moment of the civil rights movement . . . we were there when segregation was finally put to the challenge. So I have a real sense and appreciation for what the federal government can accomplish.”

For the moment, Taylor’s thoughts are on the Northeast and how it can and should function as a region. “New York and New England should find common cause and think of themselves as a country, as a distinct, new region with a distinct set of values, with its own problems and own path. The future requires we identify ourselves regionally and solve problems on our own.”

But Taylor has a more immediate to-do list that will keep him busy for the next decade. “In 1968, I never thought I’d be doing this now,” he says. “I didn’t assume I’d be alive at age sixty. Maybe I can carry on for another ten years or so, or for another three, 3-year periods.”

Taylor calls himself very “project-oriented,” and topping that to-do list are making a DVD of the “One Man Band” show, a tour of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, a series of educational videos on the web and on DVD explaining his unique guitar style, a new album of all cover tunes, and one or two more albums of original songs.

“We’re putting all these projects on the calendar,” he says. “I’d like to do these, and that’s enough. I have no other goals than to do these things.”

And as an afterthought, Taylor—whose ultimate escape is rowing on a lake or climbing a tree—adds, “I’m essentially a tree-hugger. I grew up in the woods of North Carolina in the Piedmont section. Living here in the trees is great.” [AUG 2007]

Seth Rogovoy is an award-winning music critic and editor-in-chief of Berkshire Living.

On living a low-profile life in the Berkshires:

This is a good place to be well known. I’ve never had a negative experience bumping into people

who know me because of my music. But for forty years I’ve been asking for people’s attention.

When I finally get it, it would be crazy to complain about it.

On Tanglewood:

The place is so beautiful. It has some kind of spirit, emanation, because of what’s gone on there. That sounds cosmic but people love to be there. . . . There are places that are more commercial and mercenary. You feel bad about how they treat the audience, with extra ticket charges, parking fees, even charging each person in the car. You can’t bring your bottle or thermos in—not even lemonade or iced tea or water, to say nothing of alcohol—because they want to sell you a seven dollar bottle of lemonade. And the place will often be filthy. It makes your blood boil. They’re using me as bait to mug them. Essentially Tanglewood is not a commercial place. It’s nonprofit, and its mission is musical and artistic, not commerce. And that’s good. You feel that when you are there.

On musicians taking vocal political stands:

I’m just so alarmed about this administration, I had to do something. I felt so deeply bad about it. People who never did anything political are coming out of the woodwork. But you have to be careful. The audience doesn’t come for that. I don’t write a lot of political songs. To serve up a big dish of political rhetoric . . . I need to be careful of false advertising.

Vintage photos by Henry Diltz, Courtesy James Taylor

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati