A Bend in the River

A swath of lawn stretches across the spot where the bandstand used to be. Central Block, once home to a busy grocery store, post office, barber shop, and theater, is gone now, a modest package store in its place. And where a trolley on a wooden track invited riders over the river to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a cement and asphalt bridge now hustles cars down instead. Of the mill buildings that are still left, only a few carry on with smaller, quieter operations, some having been repurposed, while others slump in ruin like crumbling brick versions of excavated Roman agoras. On this gray November morning, the only signs of life are a shop owner toweling off a streaky window and a group of teenage boys, skateboards tucked under their arms, roughhousing in front of the Corner Market.

Surveying the scene, it’s hard not to think that a hush has fallen over Housatonic, Massachusetts, a town of just 1,300 whose short, intense history is almost indistinguishable from the rise and fall of the mills that once drove its economy. Yet somehow there is an undercurrent of energy, of something about to happen. The residents of Housatonic have watched their own town go up in flames, literally, on more than a few occasions and have managed to rebuild it. Now, like the mythical Phoenix, Housatonic seems poised to rise from the ashes once more.

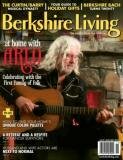

Robby Baier, a musician who, along with his wife, painter Carol Gingles, turned the historic train station on Route 183 into a recording studio and art gallery, feels the anticipation, too. “[Housatonic] might have a sleepy appearance,” he says. “There is not much of an obvious town center or a shopping district. There are two general stores and a post office and a handful of galleries that are easy to miss if you are looking out for the ‘action.’” But when visitors stick around, they might be pleasantly surprised by the gallery openings at Cosmos Troy Gallery and Lauren Clark Fine Art, an open-mike night at Deb Koffman Artspace, the free pool night at the Brick House Pub, basketball games at the “Housi Dome” (the gym next to the old elementary school), and a variety of dance and music classes at Berkshire Pulse. More art spaces are also in the works. “While it is not the ‘Soho of the Berkshires,’ as has been proclaimed in some articles,” Baier maintains, “Housatonic has a lot to offer if you are willing to spend the time exploring.”

The village of Housatonic was founded in the early 1800s as a precinct of Great Barrington. In its heyday—the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—it was a powerhouse of textile and paper production, turning out some of the country’s finest writing paper and more than half a million quilts and four million pounds of cotton warps each year. A pair of deep economic slumps, after World War II and again in the 1980s, however, nearly destroyed the town, but it revived itself again in the 1990s, largely without commerce. Still, it’s impossible to drive through the town without noticing the hulking ghosts of industrial giants past, particularly Monument Mills, which at its peak occupied 420,000 square feet of factory space in five buildings and employed five hundred people, many of them Polish immigrants imported because of their sophisticated textile work. It didn’t hurt that they also formed a cheap labor force and didn’t object to being sandwiched into tenement houses along the river. Poles, in fact, made up the vast majority of the town’s inhabitants until the 1960s. While most came in search of mill work, others, like Frank Ptak’s family, came simply to be part of an immigrant-friendly community in America.

Ptak, now eighty-four, his tall, slender frame bundled up in a thick navy cardigan and a bucket hat, is the last of the old-timers still living in Housatonic—a fact he shares without a trace of wistfulness, as if he’s just been asked for the time. Ptak’s mother was a homemaker and his father a butcher; he was born on Front Street in Housatonic, near where he lives today. As a youngster, he had no interest in the family business and showed equal indifference toward school. He joined the Navy at seventeen and for three years served as a radio operator on the destroyer U.S.S. Charles S. Sperry in the Pacific during World War II. But the bustling town he left behind—home to five barber shops, five groceries, three package stores, a shoe and a clothing store, an appliance store, and six gin mills and steeped in social traditions like the annual Halloween bonfire and community baseball games—was almost unrecognizable when he returned.

By 1946, the cash-strapped Monument Mills began auctioning off its many mill houses. “The people who bought their houses stayed,” recalls Ptak, tapping his wrinkled fingers on his kitchen table. “Some of them took jobs at [B.D.] Rising Paper. But the ones who couldn’t afford it left town to look for other work and places to live. Those of us who could bought a bunch of real estate. We knew we could sell it later.”

Parlaying his Navy-honed skills with electronics, the twenty-one-year-old Ptak became the area’s youngest retail entrepreneur, opening Housatonic Appliance Center. Fluent in Polish, he was a hit with locals. And as the first to sell and service color TVs in the southern Berkshires, he became so successful that he soon opened a second store in Lee, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, the post-World War II economic rebound didn’t last long.

Parlaying his Navy-honed skills with electronics, the twenty-one-year-old Ptak became the area’s youngest retail entrepreneur, opening Housatonic Appliance Center. Fluent in Polish, he was a hit with locals. And as the first to sell and service color TVs in the southern Berkshires, he became so successful that he soon opened a second store in Lee, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, the post-World War II economic rebound didn’t last long.

After a series of protracted labor-union disputes, Monument Mills closed for good in 1956. “Before that,” Ptak says, “everything was pretty much the same since the eighteen hundreds. When they closed, everything started to go downhill. The town just about collapsed. The older generation didn’t know anything else.” Ptak moved his flagship store to two different Main Street, Great Barrington, locations where it remained until his retirement in 1975.

Despite such difficulties, Ptak and his wife, Doris, stayed in Housatonic. They had five children; a son and a daughter both died in their youth from cystic fibrosis. Daughters Pam and Deb were one of fifteen sets of twins born to townsfolk within a ten-year period (there must be something in the water; twins are still prevalent in Housatonic today). Ptak proudly shows off a sepia photo of them in their Communion veils and dresses, made by Doris, smiles lighting their cherubic faces. Now adults, both live in the village. Another daughter, Terry, is retired from the police force in New Britain, Connecticut.

In 1963, Ptak bought his current house and its contents for $13,150. He didn’t know just how much he was getting in the bargain. In the attic, he discovered a collection of more than a thousand glass-plate photos circa 1896 to 1910, taken by the house’s former owner and town barber Fred Sauer. Ptak purchased an antique photo enlarger and taught himself how to make prints. Ever since, he’s been printing, organizing, and displaying the photos in frames he makes himself. The resulting images document the amazingly vibrant town that Housatonic was before the mills folded.

Even more amazing, Ptak can recall what’s in every shot. Leaning over prints and photo albums, he points out people, places, and businesses long departed. The way Ptak fills in details about the uniformed town marching band, the crack of a bat on ball echoing over Rising Field, catching a show at the Central Block theater, or taking the ten-cent trolley into Great Barrington, these things could be happening right now, just around the corner, instead of decades ago.

Ptak is less than thrilled about today’s Housatonic, with musicians, painters, writers, photographers, and gallery owners leading the push for a revitalization effort. He waves a hand and says, “I don’t fit into that scene. A lot of things about this town have stayed the same, but a lot has changed, like the arts community. The people have changed, too—they don’t get as friendly with each other as they used to. There are more second-home owners. It’s good that they bring new money into the town, but I think they should put their kids in the local schools.” He pauses briefly, then resumes, “You used to be able to go right into the middle of town and buy everything you need. You can’t do that anymore. There just isn’t enough business.”

As if to punctuate this sentiment, the fire station whistle blows at noon. It’s a haunting sound, a reminder of the village’s long and tortured relationship with fire. Between 1850 and 2001, no fewer than a dozen major conflagrations have razed manufacturing buildings (including the town’s original factory, Dean & Whitmore, and its successor, Housatonic Manufacturing), a theater, a post office, a church, retail stores, an inn, a lumber mill, even the town’s bandstand and part of its public park.

But the resilience of Housatonic’s residents has kept the town alive. Dawn Barbieri, who twenty-eight years ago married into the family that owned Barbieri Lumber, a mainstay of the local economy for two decades, knows something about personal toughness. A petite, soft-spoken woman with straight brown hair spilling down her back, she greets visitors from behind the desk of the Ramsdell Public Library, a stately Georgian revival building opened in 1908 between the Corpus Christi Catholic Church and the Housatonic Congregational Church on Main Street, on the site of the first house in Housatonic (the home has since been moved to High Street; the town has a tradition of moving buildings from one place to another).

of moving buildings from one place to another).

Barbieri, who has worked at the town library for nine years and is now its assistant director and program coordinator, can still remember certain pieces of the good old days—Memorial Day parades, large Polish picnics on the town green, baseball games at the now weed-choked park on Route 183—but for her, Housatonic has been marked by more recent events. The first was the 2001 arson that ravaged three of the old Monument Mills buildings, including those occupied by Barbieri Lumber. (Only a portion of a fourth building, which now houses the Berkshire Pulse dance studio, was salvaged.) She speaks about it matter-of-factly, but it’s clear she’ll be moving on to another topic, pronto. The second was the closing of Fox River Paper, which occupied the old B.D. Rising Paper mill buildings, in 2007. Hundreds of workers were laid off and couldn’t be absorbed by the building’s new tenant, the much smaller Hazen Paper Company. But the third blow, the closing of the elementary school on Pleasant Street that same year, was perhaps the worst for Barbieri. With a heavy sigh, she remarks, “Kids used to play there every day. It was so full of life, and now it’s empty.”

Undaunted, Barbieri has been part of the effort to bring new life to the town. She and a group of townspeople—Baier and Gingles among them—have lobbied hard to obtain a development grant from Great Barrington to study how to make the streets safer and more accessible, how to make the library ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act)-compliant, and how to turn the old school playground into a park. They’ve encouraged the growth of Housatonic’s new favorite sport, basketball, and initiated discussions to make the school building into an arts venue. But talks slowed when two competing organizations couldn’t bring their ideas into alignment, and reached a stalemate with the death of Alice Bubriski, the daughter of one of the town’s original Polish immigrant families and the longtime “unofficial mayor” of Housatonic.

Unlike Ptak, Barbieri sees the arts scene as integral to Housatonic’s rebirth, and she’s found her own place within it. She plays saxophone in the local seven-piece blues, funk, and groove band, Fragment Poly, and is an illustrator, calligrapher, and poet. But her main form of expression is in watercolor. “I like to paint the few farms that are left in southern Berkshire County, to record a way of life that’s vanishing,” she says. “I also like to paint distressed buildings, dilapidated old cars and tractors. It’s capturing a life that was.”

While a “life that was” still resonates throughout the town, Barbieri is encouraged to see new families settling here and people talking about ways to bring in commerce; she hopes this will lead to renewed efforts at creating affordable housing (the median house or condo price on Housatonic’s tightly built streets hovers around $230,000). As she neatens a stack of papers behind the circulation desk, flanked by display copies of Still to Mow by poet Maxine Kumin, Benazir Bhutto’s Reconciliation: Islam, Democracy, and the West, and The Lolita Principle by Julia Wagner, Barbieri ruminates over her wishes for Housatonic. “In many ways, it’s a repressed little village,” she says. “I saw it with my own kids—when they were grown, they moved away, because there’s little affordable housing and even fewer jobs. But even with everything that’s happened, the spirit of this town has stayed the same. People have such affection for what was here. It’s a great community to live in, but it can be even better—more attractive, with more places for families, business, and the arts to grow.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—the various misfortunes Housatonic has endured, its residents have become masters of reinvention. Richard Bourdon, owner of Berkshire Mountain Bakery, exemplifies this as well as anyone. As a French-Canadian music student in the 1970s, he moved to Europe. With a child on the way and not enough money to support his family, Bourdon, who always enjoyed cooking, placed an ad in a Dutch newspaper as a baker, and a new career was born. In 1985, he was recruited to teach baking at the Kushi Institute in Becket, Massachusetts. When he outgrew the space, he decided to strike out on his own.

“The first time I ever drove down through Housatonic to Great Barrington to drop my kids off at the  Steiner school, I was driving by the river and I noticed those big trees by the road,” he recalls. “The rushing water. The quietness of it. The curving of the road around the river. It seemed like you were going into a small town that had more of a European flair.”

Steiner school, I was driving by the river and I noticed those big trees by the road,” he recalls. “The rushing water. The quietness of it. The curving of the road around the river. It seemed like you were going into a small town that had more of a European flair.”

Bourdon, father of five and now grandfather of three, all of whom still live in town (except for a daughter in Montreal and a son in Northampton), opened his first small bakery, funded with cash from three investors that he eventually bought out in 1985. His sourdough breads fairly flew out of the ovens, and within six months he went from making two to three thousand loaves to eight thousand per week. He quickly required a larger facility and moved into the old mill building on Route 183 that Berkshire Mountain Bakery inhabits to this day. By 1987, he was up to ten thousand loaves. Today, they don’t make ten thousand loaves anymore, but have instead chosen to diversify, also making frozen pizzas, toasts, cookies, and the pizza crust for Baba Louie’s in Great Barrington. But Bourdon retained his focus on the quality of the product. “I committed to bringing better food into this world,” he says, his Québecois accent still apparent. “I don’t make sourdough bread to uphold a tradition, but because I went into it with a question about what works best. What you have in the end is more than what I had in the beginning. It’s healthier, and it tastes better.”

Bourdon is in his element tromping around the bakery—lined with rolling racks and heavy machines that look like something out of a mad scientist’s laboratory—and discussing the technicalities of bread making. He could do without the business end of things—evidenced by his lack of a cash register (“I don’t have enough room on the counter,” he argues, and instead uses a cash box)—and positively detests marketing, though he acknowledges it’s a necessary evil. “Staffing’s always been difficult,” he comments, carrying a mammoth tin of olive oil from one storage rack to another. “Housatonic is a quiet town. People don’t look for jobs here. We have a lot of drive-through traffic in the summer, but most don’t stop.”

Bourdon enjoys the growing presence of the arts community and might even like to see the mills turn into something like MASS MoCA in North Adams, but he knows that won’t happen until a business infrastructure is put in place to support it. “We need new businesses—all kinds—but there’s no way it can happen right now. The ones that are here are having a hard enough time, especially the galleries. We need stores, restaurants—if you have to get back in the car and go to Great Barrington just to get something to eat, that’s a problem.”

Still, Bourdon, like many Housatonic long-timers, isn’t going anywhere. “My whole life happens in a half mile,” he shares. “There is something beautiful, comfortable here. It’s a town with no parking meters. People are pretty friendly. We don’t have nearly the problems with congestion that some of the other towns do in the summer. The arts scene is growing, which is nice. Things will happen in time. They always do.” BL

Robin Catalano is a contributing editor to Berkshire Living.

THE GOODS

Aberdale’s

10 Depot St.

Housatonic, Mass.

Berkshire Mountain Bakery

367 Park St./Route 183

Housatonic, Mass.

www.berkshiremountainbakery.com

Berkshire Products

www.berkshireproduct.com

Berkshire Pulse

410 Park St./Route 183

Housatonic, Mass.

www.berkshirepulse.com

Brick House Pub

. N./Route 183

Housatonic, Mass.

Corner Market

226 Pleasant St.

Housatonic, Mass.

Cosmos Troy Gallery

135 Front St.

Housatonic, Mass.

www.cosmostroy.com

Deb Koffman Artspace

In Words Out Words, open mike

First Tuesday of every month

.

Housatonic, Mass.

www.debkoffman.com

Front Street Gallery

129 Front St.

Housatonic, Mass.

Housatonic Curtain Company

430 Park St

Housatonic, Mass.

www.countrycurtains.com

Jacks Grill

1063 Main St.

Housatonic, Mass.

www.jacksgrill.com

Lauren Clark Fine Art

./Route 183

Housatonic, Mass.

www.laurenclarkfineart.com

Ramsdell Public Library

10.

Housatonic, Mass.

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Propeller

Propeller Reddit

Reddit Magnoliacom

Magnoliacom Newsvine

Newsvine Technorati

Technorati